All Is Number: What the Pythagoreans Actually Meant

Before words, before images, before thought as we know it—there is number.

When Pythagoras said “all is number,” he was not speaking in metaphor. He was making a precise claim about the structure of reality: that relationship, ratio, and proportion are more fundamental than substance. That the universe is not made of stuff but of pattern. That the pattern is mathematical.

Twenty-six centuries later, modern physics has arrived at essentially the same conclusion—though it took the longer route.

The Discovery

The story begins with a blacksmith’s shop. According to tradition, Pythagoras noticed that hammers of different weights produced different tones when they struck the anvil, and that the tones that sounded harmonious together corresponded to simple whole-number weight ratios. He went home and verified the principle on a monochord—a single string stretched over a resonating chamber.

The results were extraordinary. A string stopped at its midpoint (ratio 1:2) sounded the octave—the same note, one level higher. Stopped at two-thirds its length (ratio 2:3), it produced the perfect fifth. At three-quarters (ratio 3:4), the perfect fourth. These three intervals—and these alone—were considered “perfect consonances” by the ancient world.

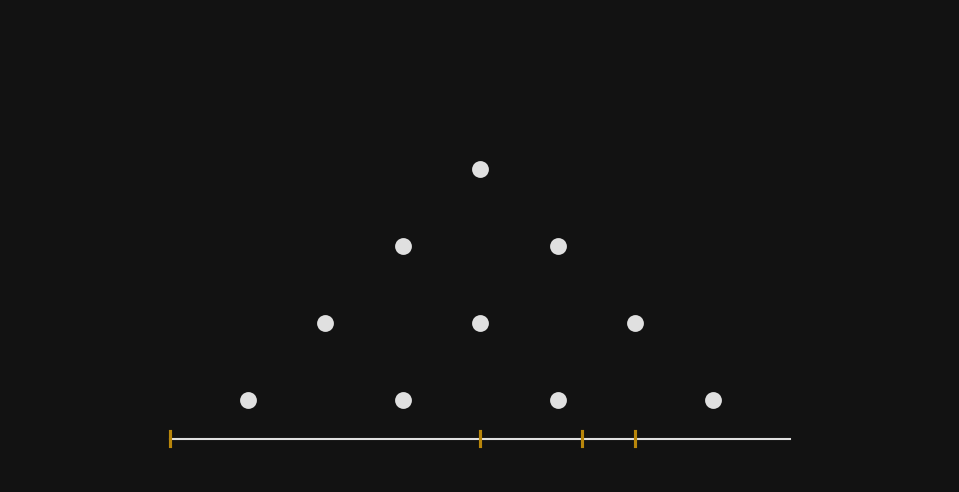

The first four numbers (1, 2, 3, 4) contained all of music. The Pythagoreans arranged them in a triangle called the tetractys—ten dots in four rows—and swore their most binding oaths by it: “By him who gave us the tetractys, which contains the fount and root of ever-flowing nature.”

Number as Quality

For the Pythagoreans, numbers were not mere quantities. Each number had a quality, a character, a meaning.

One is unity—the source, the undifferentiated. Before the first division, before the first distinction, there is the One. It is not a number among numbers; it is the principle from which number arises.

Two is polarity—division, the first Other. The moment there is Two, there is relationship, contrast, the possibility of dialogue. Two is the condition for love, for conflict, for knowledge. You cannot know the One without Two, because knowing requires a knower and a known.

Three is reconciliation—the child of One and Two, the first synthesis. If Two is tension, Three is resolution. The triangle is the first closed shape. Three is the minimum for structure, for story (beginning, middle, end), for harmony (root, third, fifth).

Four is stability—the square, the solid, the foundation. Four directions. Four elements. Four seasons. The tetractys sums to ten (1+2+3+4=10), and ten was considered the number of completeness, the return to unity at a higher level.

These are not arbitrary associations. They are intrinsic to number itself. Numerology, rightly understood, is the contemplation of these qualities.

Plato’s Hidden Music

Ernest McClain, in his extraordinary The Myth of Invariance (1976), demonstrated that Plato encoded an entire cosmology in musical mathematics. The “sovereign number” of the Republic, the world-soul of the Timaeus, the cities of Magnesia and Atlantis—all are musical-mathematical constructions. Plato was hiding the mysteries in plain sight, knowing that only those with ears to hear would understand.

Plato insisted that tuning theory be studied “not for the sake of practical harmonics but to learn which numbers are concordant and which not, and why.” He was not interested in building better lyres. He was interested in understanding the structure of existence. The musical ratios were, for him, a window into the Forms—eternal patterns that govern all manifestation.

The musical proportion 6:8::9:12 was the cornerstone of Pythagorean philosophy. Between 6 and 12 (the octave), there are two means: the arithmetic mean (9) and the harmonic mean (8). These divide the octave into a fourth (6:8, or 3:4) and a fifth (8:12, or 2:3). All of Greek music theory—and by extension, all of Platonic cosmology—rests on this proportion.

Why It Matters Now

“All is number” does not mean reality is cold or mechanical. It means reality is structured, meaningful, intelligible. The fact that the universe can be described mathematically is evidence that it is not random—it is ordered, and that order is knowable.

The ear perceives mathematical relationships directly, translating number into sensation. Music is audible mathematics; mathematics is silent music. When you hear a chord and feel something—that catch in the chest, that sense of rightness or tension—you are feeling number. You are feeling the structure of existence itself.

To learn mathematics is to learn the language in which the cosmos speaks.

Further Reading

Ernest McClain, The Myth of Invariance (Nicolas-Hays, 1976)

Ernest McClain, The Pythagorean Plato (Nicolas-Hays, 1978)

Walter Burkert, Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism (Harvard, 1972)

Charles Kahn, Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans (Hackett, 2001)

Kitty Ferguson, The Music of Pythagoras (Walker, 2008)