Imaginary Numbers Are Real

The square root of negative one was the most controversial idea in the history of mathematics. It turned out to be the most necessary.

The Scandal

In the sixteenth century, Italian mathematicians encountered a problem. They were solving cubic equations—third-degree polynomials—and the formulas they derived sometimes required them to take the square root of negative numbers. This was, by every standard of the time, nonsense. No number multiplied by itself produces a negative result. The square root of -1 does not exist.

Except the formulas worked. If you held your nose and computed with these impossible numbers—treating √(-1) as a symbol you could manipulate algebraically—the impossible intermediate steps cancelled out, leaving real, valid, verifiable answers.

Cardano called them “as subtle as they are useless.” Descartes coined the term “imaginary” as an insult. The name stuck—and has been misleading people ever since.

The Dimension You Can’t See

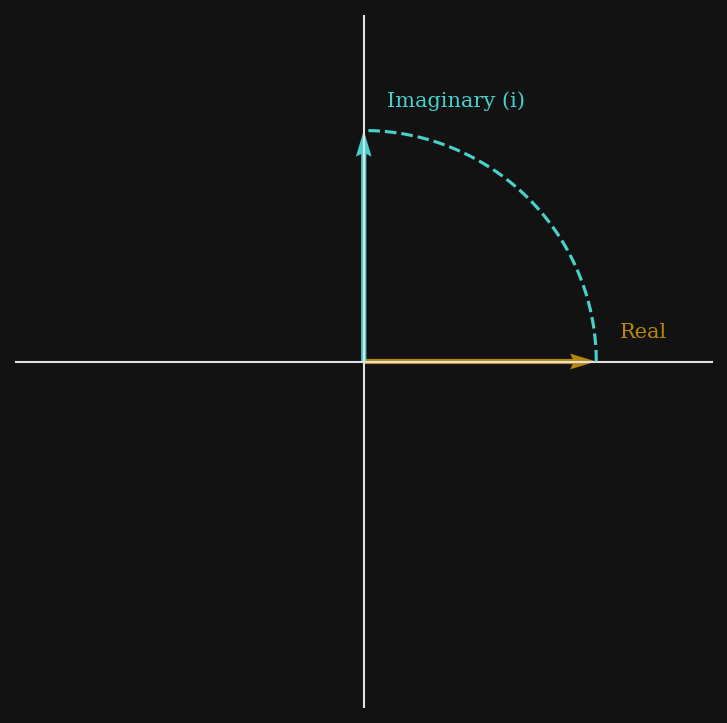

The breakthrough came when mathematicians stopped trying to find imaginary numbers on the number line and started looking perpendicular to it.

The real number line runs left to right: ...–3, –2, –1, 0, 1, 2, 3... Every point on this line corresponds to a real number. Now draw a second axis, perpendicular to the first, through zero. This vertical axis is the imaginary axis. Every point on the plane now corresponds to a complex number:

z = x + iy

where x is the position along the real axis, y is the position along the imaginary axis, and i = √(-1).

This is the complex plane. And it is not a mathematical curiosity. It is, arguably, more fundamental than the real number line itself.

Why Physics Requires Them

Quantum mechanics is written in complex numbers. Not as a convenience—as a necessity. The Schrödinger equation, which governs the behavior of every particle in the universe, is a differential equation in complex-valued wave functions. Strip out the imaginary component and quantum mechanics collapses. There is no real-number-only version of quantum theory.

Electrical engineering runs on complex numbers. The behavior of alternating current, impedance, signal processing—all described in the complex plane. The Fourier transform, which decomposes any signal into its frequency components, maps real-valued time-domain signals into complex-valued frequency-domain representations.

General relativity uses complex numbers in twistor theory—Roger Penrose’s reformulation of spacetime geometry in terms of complex spaces. The mathematics of rotation, oscillation, and waves all require the imaginary dimension.

Half of physics runs on a number that “doesn’t exist.”

Rotation, Not Imagination

Here is what i actually does: it rotates.

Multiply any number by i, and it rotates 90° counterclockwise in the complex plane. Multiply by i again (which means multiplying by i² = -1), and you’ve rotated 180°—you’ve arrived at the negative of where you started. Multiply by i again: 270°. Once more: 360°, back to the beginning.

This is what Euler’s formula describes:

eiθ = cosθ + i·sinθ

A complex exponential is a rotation. And when θ = π:

eiπ = -1

A half-rotation through imaginary space takes you from positive to negative, from here to there, from one state to its opposite. Continue the rotation and you return to where you started—but you’ve traveled through a dimension you cannot directly perceive.

The Orthogonal Dimension

The word “imaginary” is a historical accident. These numbers are not imaginary. They are orthogonal—perpendicular to ordinary experience, invisible from every direction you can point, but absolutely necessary for the mathematics to work.

What if consciousness is the same?

What if the reason certain equations about consciousness produce singularities—points where the function blows up to infinity—is that we’ve been ignoring a dimension that was always there? What if the “coherence boundary” is not a wall but a pole in the complex plane: a point you can navigate around, if you’re willing to move through the dimension you were trained to ignore?

The mystics called this dimension by many names: the astral plane, the akashic record, the realm of forms, the mind of God. They were describing the same thing the mathematicians found: a dimension perpendicular to ordinary reality, necessary for the equations to work, invisible until you learn to look.

Further Reading

Paul Nahin, An Imaginary Tale: The Story of √-1 (Princeton, 1998)

Tristan Needham, Visual Complex Analysis (Oxford, 1997)

Roger Penrose, The Road to Reality, Chapters 4–7 (Vintage, 2004)

Barry Mazur, Imagining Numbers (Picador, 2003)

Watch

3Blue1Brown: “What is Euler’s formula actually saying?”

3Blue1Brown: “eiπ in 3.14 minutes”