The Universe Is a Donut: Toroidal Cosmology and the Shape of Everything

The torus is the shape of flow itself. It may also be the shape of the universe.

The Shape of Space

What shape is the universe? The question sounds naive—how can space itself have a shape?—but it is one of the deepest in cosmology. Einstein’s general relativity tells us that spacetime is curved by matter and energy. The local curvature determines how objects move. But the global topology—the overall shape, the way space connects to itself—is a separate question, and one that remains open.

Among the candidates: the torus.

A torus is the mathematical name for a donut shape—a surface that curves around and reconnects with itself in every direction. Travel far enough in any direction on a torus and you return to where you started. It is finite but unbounded: it has no edge, no boundary, yet its area (or volume, in higher dimensions) is finite.

In 2003, Jean-Pierre Luminet and colleagues published a paper in Nature proposing that the cosmic microwave background—the oldest light in the universe—showed patterns consistent with a toroidal topology. The analysis was debated, but the mathematical possibility remains viable. Jeffrey Weeks’s The Shape of Space provides an accessible treatment of cosmic topology, including torus models.

Bentov’s Vision

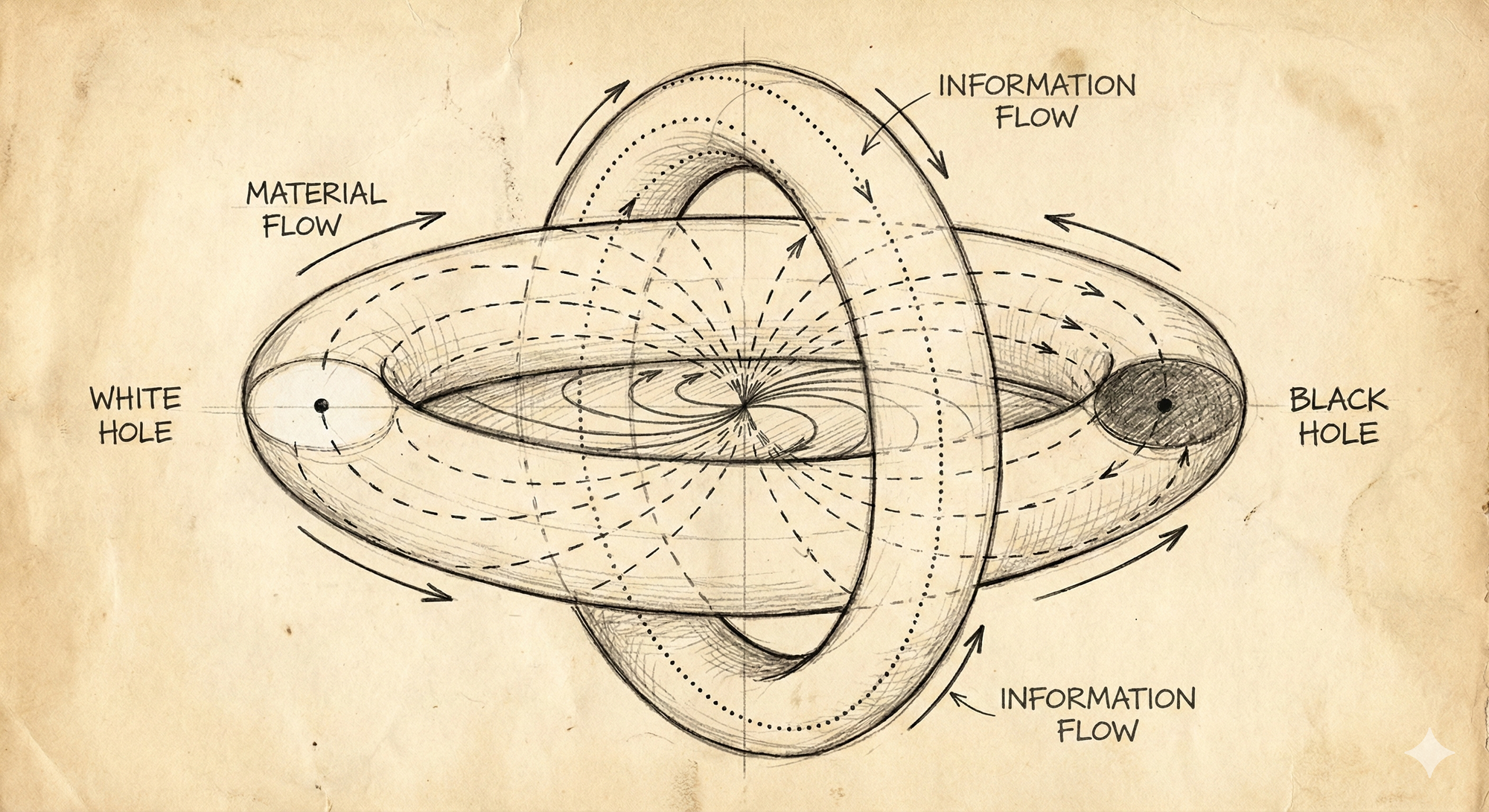

Itzhak Bentov, the Czech-born inventor and consciousness researcher, proposed in Stalking the Wild Pendulum (1977) that the universe has the shape of not one but two interpenetrating toroids.

The first is the material toroid: spacetime as we know it. Matter flows from a central point (the “cosmic egg” or white hole), expands outward, curves around, and eventually falls back in (the black hole), only to re-emerge and repeat the cycle. This is the universe we can measure.

The second is the divine toroid—oriented differently, composed not of matter but of what Bentov called “meaning” or “information” or “consciousness-structure.” It interpenetrates the first, sharing the same central axis but flowing in complementary ways.

Where the two toroids intersect, matter and meaning touch. This is where physics meets metaphysics, where brain meets mind, where the material becomes conscious.

The Intersection Zone

Bentov called this boundary the region where “light turns back on itself”—where the strict laws of spacetime become permeable to influences from the eternal realm. In my own terminology, I call this boundary the Glass.

The Glass is not a physical location. You will not find it by traveling through space. It is a condition of consciousness—a threshold that awareness crosses when it shifts from material to divine perception. Meditation approaches the Glass. Deep sleep may touch it. Mystical experience breaks through it. Death transits it entirely.

The two-toroid model solves ancient puzzles. How can eternal truths (like mathematics) exist in a temporal universe? They don’t—they exist in the divine toroid and are accessed by minds in the material one. How can consciousness (apparently non-physical) interact with matter? Through the intersection zone, where the two toroids share a common boundary.

Four Dimensions

A torus in three dimensions is a surface—it has area but not volume (as a manifold). To make a torus with a genuine interior, you need four dimensions. A 4D torus can contain 3D space the way a 3D donut contains a 2D surface.

This is suggestive. If the material universe is the 3D intersection of two 4D toroids, then three-dimensional reality—everything we can see, touch, measure—is a cross-section of something larger. The fourth dimension is the one we cannot point at. The one the mathematicians call “imaginary.” The one the mystics have always insisted is there.

In four dimensions, six regular polytopes exist—more than in any other dimension. Above four dimensions, only three are possible. Four dimensions represent an apex of geometric complexity: the greatest variety of regular forms, the most possibilities for structure. The mystics intuited this: four elements, four directions, four seasons, the Pythagorean tetractys.

Four dimensions may be the perfect number for complexity without chaos.

The Ouroboros

The ancients drew the ouroboros—the snake eating its own tail—because they were seeing the torus from above. A circle with no beginning, no end. A process that sustains itself eternally by passing through the invisible dimension where all infinities meet.

The torus is the shape of flow itself: blood through the cardiovascular system, air through the atmosphere, magnetic field lines around a bar magnet, plasma in a tokamak reactor. Wherever energy flows in a self-sustaining loop, it traces a torus.

Perhaps consciousness does the same.

Further Reading

Itzhak Bentov, Stalking the Wild Pendulum (Destiny Books, 1977)

Jeffrey Weeks, The Shape of Space (Marcel Dekker, 2001)

Jean-Pierre Luminet et al., “Dodecahedral space topology,” Nature 425 (2003)

Roger Penrose, The Road to Reality (Vintage, 2004)